Original language: español

Year of publication: 2024

Valuation: Highly recommended

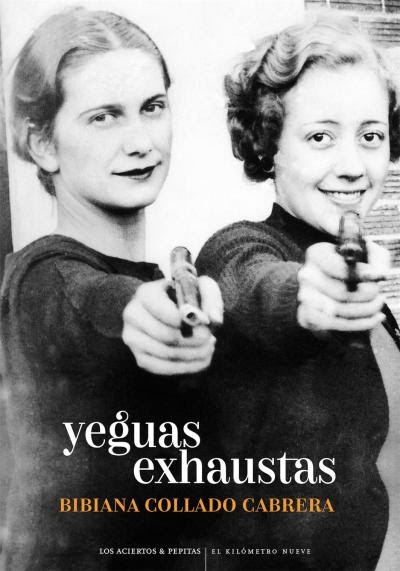

I think it is quite evident that in recent years the voices that coexist and dialogue in Spanish literature have been diversifying (although obviously there is still a long way to go), firstly and above all due to the necessary incorporation not only of works by female authorship, but also of texts that present female (and feminist, which is not necessarily the same) experiences and perspectives. Within this growing diversity of voices and experiences, exhausted mares offers a very interesting intersection, and much less common than it should be common, I think: that of the gender perspective with the class perspective (or consciousness). In a fundamentally bourgeois literature (aren’t they all), aims to rescue and vindicate the memory and dignity of those (and especially those) below, starting from a personal narrative, but with a clear intention of representativeness.

Because these are, without a doubt, the two coordinates from which Beatriz’s experience can and should be understood, and also the novel’s own position in relation to the Spanish literary canon: class and gender. Beatriz is a character and narrator radically situated in her class, in her origins as a house-cleaning mother and from an Andalusian immigrant family in Valencia. Their references, their tastes, their training and also their conflicts and doubts come from that class mark, which may be apparently undetectable, but which resurfaces when it comes to separating those who have the right to occupy certain spaces and certain positions of power or of speech, of those who do not have that privilege, whether in the academic, artistic or literary world. Hence, also, many of the doubts, fears and regrets that the narrator feels and writes down in the text as she writes it: whoever occupies a subordinate position is forced to doubt their ability or legitimacy to speak or to say according to what things. Hence, also, the conversational tone of the book, which may be shocking at first, for seeming “unliterary”, but which I believe also responds to a conscious questioning of, precisely, what we call literature and art (and by whom and for whom that art is created).

In addition to class, the second coordinate that the novel crosses is gender: Beatriz not only feels the conditions derived from being of working and rural origin, but also those related to being a woman in a patriarchal society and in which violence (of various kinds) continues to be a weapon of subjugation of women. In fact, a relevant part of the novel shows the abusive relationship maintained by Beatriz with a man older than her, who uses all types of tools of manipulation and control, from humiliation and infantilization, to shouting or the threat of violence. physical. The novel does not explain exactly how or when Beatriz manages to break that toxic and destructive bond; Luckily, a series of interspersed chapters, published on pages of a darker tone than the rest, show us some time later, at the time of writing the text we are reading, in a healthy relationship with another man.

I don’t want to go into more detail, among other things because next comes the interview with Bibiana Collado, who says very interesting things. I end, thus, recommending that you read exhausted maresa more than welcome addition to the chorus of voices that make up contemporary Spanish literature.

Source: https://unlibroaldia.blogspot.com/2024/04/resena-entrevista-yeguas-exhaustas-de.html