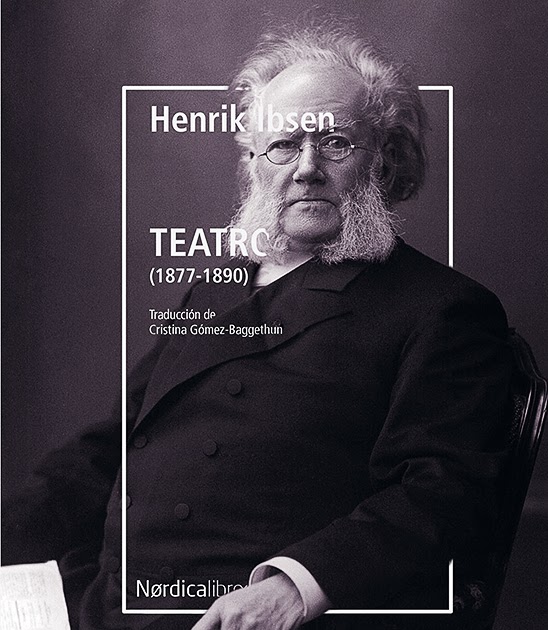

Idioma original: Norwegian

Original title: Repeaters

Translation: Cristina Gómez-Baggethun (in Spanish for Nórdica)

Year of publication: 1881

Valuation: Alright

It is always somewhat difficult to review plays in their literary format, as one must mentally recreate settings and spaces, and a large part of the text focuses on dialogues between characters, so the reader must be willing to almost form part of an imaginary cast of actors and mentally enter the setting. And the success of such an undertaking depends largely on the story itself.

In this work, written at the end of the 19th century, there are only five characters involved and it is divided into three acts corresponding to the usual narrative moments (introduction, middle and end). The story begins with a scene between Regina (Mrs. Alving’s assistant) and her father, who tries to convince her to leave the home where she is doing the housework and go live with him to work in a kind of inn for sailors. The girl rejects the proposal because she does not trust the business that her father is planning to do or him, since he is someone with a somewhat erratic life. In parallel, we see how Osvald, Mrs. Alving’s son, has returned from a trip abroad and finds his mother talking to the town reverend about the construction of an asylum financed by her. The appearance of the son and the details of his life abroad alarm the reverend, because the young man’s mentality has changed since he left, abandoning the most archaic and closed customs to see society from a more open point of view; Thus, Osvald defends that couples can have children without getting married and live together in the same home, ideas with which his mother agrees but which irritate the reverend, who disputes his ideas and concepts about freedom, stating that “in this life it is pure rebellion to hope for happiness. What right do people have to be happy? No, madam, what we have to do is fulfill our duty!” Old-fashioned ideas that he reaffirms when speaking to his wife about her late husband and the life of excess that he led, saying that “a wife must not set herself up as a judge of her husband. You had the obligation to humbly bear the cross that a higher will had considered appropriate to grant you.” From this staging and heated conflict, the action develops in a continuous contrast between mentalities and ideologies to which are added situations from the past of those involved that provoke no few discussions and revelations that put at risk the fragile family and social balance of the characters.

As he has shown on many occasions, Ibsen knows how to find the social and moral conflicts of his characters and subjects them to moments of confrontation, thus showing the customs of a society that is opening up to new ideas and world views. We cannot forget that we are at the end of the 19th century, a time when Ibsen’s ideas collided head-on with a society where the family model (with a great influence of religion) was little less than untouchable, so his courage and daring give it even more value than the text itself deserves. Therefore, despite the fact that it is not one of his best works, Ibsen must always have a prominent place in our reading baggage, because the influence of his work in the history of drama is unquestionable.

As one of the protagonists says in the text, in the middle of a confession to the reverend, “I have had the sensation of seeing ghosts. Although I would say that we are all ghosts (…) and not only because we carry the legacy of our parents. We also have many old and dead opinions.” And she is not wrong, because the legacy of our past is still present in us, sometimes with noble and current values, but also with closed and archaic mentalities that should be buried so that they do not appear and prevent progress in rights and freedoms.

Source: https://unlibroaldia.blogspot.com/2024/09/henrik-ibsen-espectros.html