Original language: japanese

Original title: Potoreito in jazu (Portrait in Jazz)

Translation: Juan Francisco González Sánchez

Year of publication: 2020

Valuation: disappointing

If you think that reading all of Haruki Murakami’s books translated into Spanish would take more time than watching all the chapters of One Piece, you should consult the catalog of his works in Japanese. Being one of the most popular Japanese writers, publishers do well to get the most out of him, even if they go to absurd extremes such as publishing books like “Learn English with Haruki Murakami.” Along these lines, the Spanish translation of short texts comes to us, halfway between the essay and the Facebook post, where grandfather Murakami shares his ideas about the world of jazz, taking a musician as the axis of each text. iconic of that golden era of American jazz.

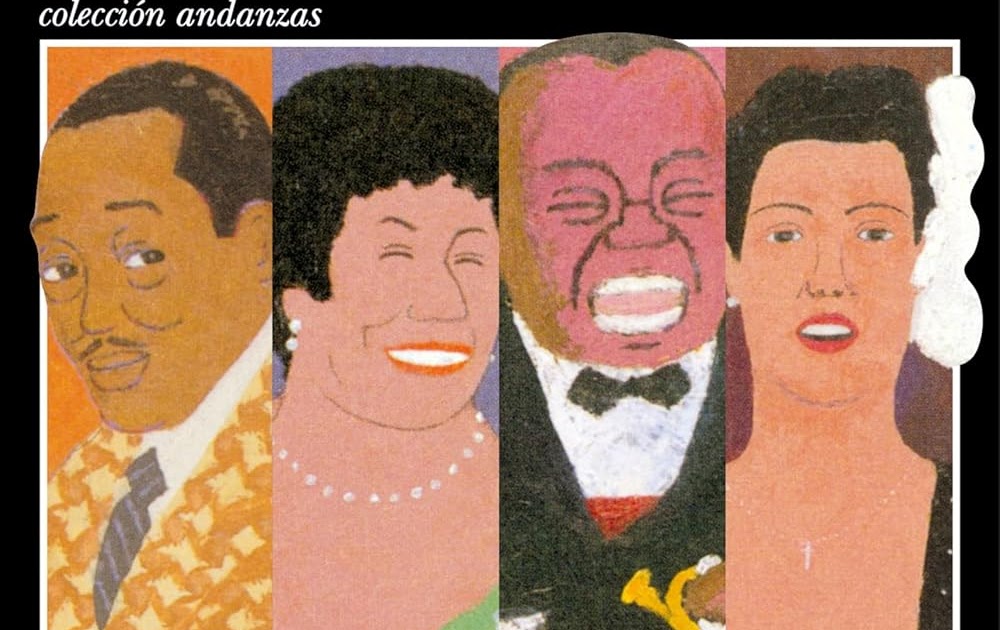

The book presents more than 50 sketches, each accompanied by a portrait of the corresponding musician, drawn by Makoto Wada, an illustrator who had already collaborated with Murakami on other works and who was the illustrator of the cover of the literary magazine Shūkan Bunshun for more than 40 years. In addition, each entry includes a photo of a vinyl, a recommendation to get to know the musician and understand a little more what Murakami is expressing.

A question I asked myself after reading a few chapters of the book was: Why make a book specifically for this? With the words I chose in the previous paragraph you will have already realized that, in my opinion, this book could very well have been a blog (ha!) or an Instagram account where Murakami recommended the albums he likes. You could even easily include audios and videos, essential elements when it comes to music.

Speaking specifically of the text, no matter how fond of jazz he is (we all know that he had a jazz club), it is clear that Murakami is not a musician. Although this book does not attempt to give us technical details and the target audience is, like Murakami, jazz fans, the way in which these ‘portraits’ are approached is too superficial. On many occasions, interesting episodes from the musicians’ lives are not even recounted, only the most frivolous impressions: “it is undoubtedly incredible,” “the bass was deep like a forest.” Murakami has the nerve to, in the chapter dedicated to Charlie Parker, start talking about something else and, at the end, tell us: “Ah, sorry, I didn’t even say anything about Charlie Parker.”

In order not to remain in the realm of the abstract, see how these topics are addressed by saxophonist and YouTuber Jay Metcalf of BetterSax in one of his videos (“Top 10 alto sax players of all time”), talking about Charlie Parker:

Let’s go with the most obvious one first, because without it, this list wouldn’t even be possible. Of course, I’m talking about Charlie Parker, Bird. Considered the father of Be-bop, the innovator, the instigator, the creator. He is, without a doubt, one of the greatest musical geniuses of the 20th century. So ahead of his time that if he played today, his music would sound contemporary. It is ironic that many musicians who came after him are accused of plagiarizing Charlie Parker, when in reality, Bird’s technique is still unmatched. As far as I know, this is the only video of Bird performing live (proceeds to show us a clip of Parker playing). Did you see that? The octave key got stuck and had to be returned to its place (This is what I mean, someone who knows what they are talking about can point out interesting details). Parker played his custom ‘King Super 20’ saxophone, which is on display at the National Museum of African American History and Culture. (another interesting detail). Then he gives us more technical details (playing some parts himself). As I said, I understand that this is not the point of Murakami’s book, but if not, I don’t understand what it is.

Another notable example of a text developed around a musician is Cortázar’s The Pursuer. An incredible story, mandatory for every jazz fan.

Additionally, Makoto Wada, the book’s illustrator, provides a visual dimension that could have enriched the experience if it had been integrated more coherently with the texts. Personally, I don’t really like his naïve style, at least not in this book, but I understand its appeal. However, they often do not reflect the depth or complexity of the musicians (Miles Davis and Stan Getz are portrayed very similarly). A more realistic or expressive style might have better complemented Murakami’s essays, offering a more meaningful connection between image and text.

In my opinion, this book was just a whim of Murakami and/or a business for the publisher. Being a jazz fan myself, this book was really a disappointment. Both in text and visually, Portraits of Jazz fails to capture the essence of the great musicians of the genre, remaining in a superficiality that does not satisfy either casual followers or connoisseurs of jazz.

Other works by Haruki Murakami in ULAD: Kafka on the shore, What I talk about when I talk about running, South of the border, west of the Sun, The death of the commander. Book I and II, What I Talk About When I Talk About Writing, The Elephant Disappears by Haruki Murakami, The Years of Pilgrimage of the Colorless Boy, After Dark, Tokyo Blues,

Source: https://unlibroaldia.blogspot.com/2025/01/haruki-murakami-y-makoto-wada-retratos.html