Original language: español

Year of publication: 1981

Valuation: Essential

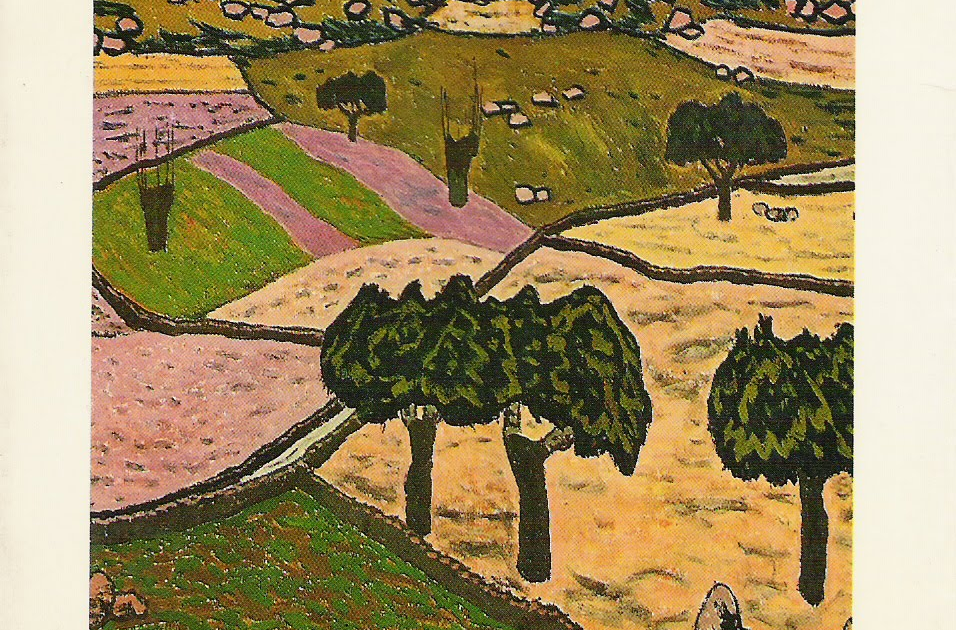

I really believe that the work needs little introduction, because it is already a classic of Spanish literature, and also because the film adaptation by Mario Camus has left us an indelible memory of some of its scenes (like that immense Paco Rabal repeating “milana bonito, pretty kite”). In any case, here is a quick summary: in a pasture that is never clearly located, but is located near the border with Portugal (in Castilla or Extremadura, therefore) lives a family of farmers composed of Paco, the Bajo ; his wife, Régula; his children, Rogelio, Quirce, Nieves and Charito, the disabled Niña Chica; and Réugla’s brother, Azarias, who also has some type of disability. Their destinies are marked by the will of their “little gentlemen”: Mrs. Marchioness, Mr. Iván or Miss Miriam, who treat them, especially in the case of Iván, with a mixture of disdain, paternalism and cruelty, in an atmosphere of misery and symbolic and material violence.

Beyond this brief summary, which could place the novel in the realm of tremendousism and/or social realism of the 50s or 60s (despite having been published, I insist, in 1981), this novel rises to another level. level thanks to the creation of a unique narrative voice: a narrator who is not a character, but who identifies with the characters and transmits his thoughts and speeches to us, integrated into very long sentences (each chapter only has one period, the final period ), in a very Saramagian free indirect style. This voice mixes the resources of orality (“let’s see, natural, as they say…”) adopted from the characters, with other fragments of a dense lyricism (“the tawny owl exercised the strange

fascination of the abyss, a kind of attraction enervated by panic, in such a way that when he stopped in the middle of the mold, he clearly heard the harsh beating of his heart”), and with the usual lexical richness of Delibes, especially when it comes to to the natural world of the Castilian countryside, thus placing himself, forgive me if I exaggerate, at the level of a García Márquez in terms of stylistic mastery.

There is no doubt, on the other hand, that this novel is a criticism, almost a satire, of the despotism and feudalism that dominated (and I don’t know if it still dominates) certain areas in Spain: Mr. Iván is “the master of the donkey.” , as the doctor says, and he can do with his servants, his animals, and his possessions whatever he wants, whether it be forcing Paco the Short to walk with a broken ankle, or blinding all his pigeons by tearing them out. eyes, or having an affair with Purita, the wife of Pedro, the Périto.

Meanwhile, on the other side, this absolute, almost medieval power, is accepted with resignation by Paco, el Bajo and by Régula (“ae, to command, that’s what we are for” is their leitmotif), while the new generations, perhaps because Delibes wanted to leave a certain glimmer of hope, show their discomfort or dissatisfaction with this state of things (“none of you go out to your father,” says Mr. Iván to Nieves, who is also complaint that “young people find it difficult to accept a hierarchy”). Perhaps in fact the greatest defect that can be pointed out to the novel is that it is Manichean in its presentation of the characters, becoming something like a Mrs. Perfect from the end of the 20th century; In any case, it is not a defect, this Manichaeism, that prevents the enjoyment of the novel but perhaps quite the opposite, especially taking into account its outcome, which I will try not to spoil.

There is another aspect of the novel that I found very interesting, now that I have reread it many years after my first reading: the relationship of the characters with nature, and in particular with the animal world. I would say that Delibes proposes in the text a gradation in the integration of human beings in their natural environment, which goes from Azarias, constantly compared to a puppy, and who has the ability to empathize and communicate with his “beautiful kites”, to the Mr. Iván, whose relationship with nature is either extractive (profit through agricultural and livestock exploitation) or destructive (through hunting, his favorite hobby). In the middle would be characters like Paco, the Bajo, also compared to a dog due to his sense of smell (and his submissive character), or of course the Niña Chica, who is several times ambiguously identified with Azarias’ kite. The separation between the human and the animal, Delibes seems to imply, is not radical, but progressive, and it depends on us how we define and confront it.

In the end, and partly thanks to the absence of a clear geographical and chronological location, Delibes proposes in The Holy Innocents a kind of parable about Spain, its inequalities and its miseries. The fact that it was already published in democracy, although set during Francoism, may be an attempt to draw attention to the continuities that, today we know very well, exist between both regimes. In any case, The Holy Innocents It is a masterpiece. Read it, if you haven’t already. For your good.

Source: https://unlibroaldia.blogspot.com/2024/10/miguel-delibes-los-santos-inocentes.html