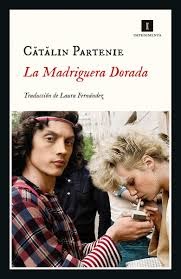

Idioma original: English

Original title: The Golden Burrow

Translation: Laura Fernandez

Year of publication: 2020

Valuation: Recommended

In December 1989, shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Nicolae Ceaușescu was arrested in a far-fetched operation, tried at top speed and executed. Considered for years a rebel in the Soviet bloc, his government drifted towards megalomania and a cult of personality, the latter element which, I must confess, I find particularly repugnant, especially when it is encouraged by the circles of power, even more so when it is assumed by the citizens, or part of them.

In the throes of the regime, some young people in Romania, like in other parts of the world, are drawn to music. There are not many options, censorship only allows music uncontaminated by Western fashions, and only a few local groups can be heard, considered harmless, and I suspect very bad. The kids manage to get hold of some European or American records on the black market and buy cheap drums or guitars with which to learn to play or, at most, perform in some tourist hotel thanks to some discreet accomplice. It seems that these young people are completely outside of political and social reality, they lock themselves in their bubble, only interested in copying Deep Purple riffs or improvising beats with their drumsticks. Uncommitted youth, isolated in their golden burrow with their musical dreams and their little sexual adventures, oblivious to the shortage of food and the winds of history.

This is how Cătălin Partenie’s modest and pleasant story is constructed, a light and pleasant narrative that draws a picture of a youthful world barely disturbed by the pathetic squeamishness of the established power, assumed as natural obstacles to which one must submit, or jump over when possible, as if they were parental prohibitions.

But this grey and relatively suffocating environment gradually permeates the lives of the young people, and the narrative becomes filled with shadows. The gradation is almost imperceptible and is one of the book’s notable values: the castrating nature of this self-absorbed regime first penetrates the older boys, who begin to make risky decisions. The option is not to fight, or even to show disagreement, but to flee, seeking the nearest borders where restrictions are supposed to not exist. The idea is simply to escape to where they can listen to and play the music they like, as simple as that, although there is much more content behind it than they themselves believe.

In this process, seen from the still naive perspective of a teenager, historical events begin to emerge, and in this way the short story of the young idealists focused on music becomes an indirect chronicle of the moment. With what seems to be an important autobiographical component, the book gains weight without detaching itself from the subjectivity of the narrator, which gives rise to a very well-balanced counterpoint that could be what best defines the text. The young man always tells what he feels and observes but, although he is not even aware of it, his field of vision is increasingly broader and what matters to him little by little is transferred from himself and his most immediate environment to the social reality of the historical moment. A convincing drawing of how inevitably the naivety of youthful dreams ends up being shaken by the passage of time.

Source: https://unlibroaldia.blogspot.com/2024/08/catalin-partenie-la-madriguera-dorada.html