Idioma original: Valencian

Original title: Mireia

Translation: Purification Mask

Year of publication: 2022

Valuation: recommended / highly recommended

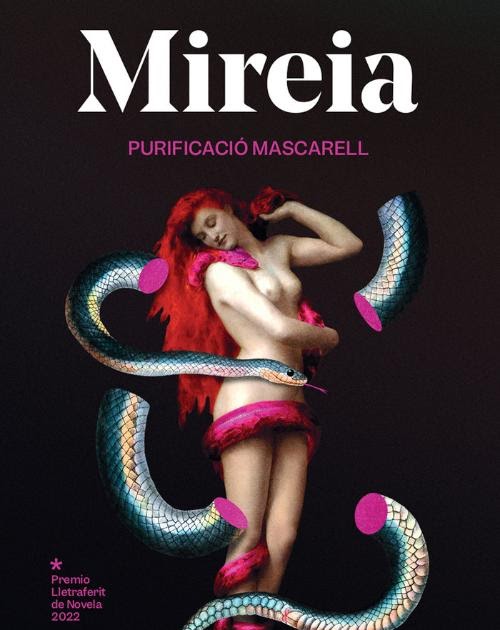

The cover of Mireia (which is maintained, with slight variations, in the original Valencian and in the Castilian version) serves to introduce some of the themes of the novel: it is about Liliththe painting by John Collier that portrays the mythical “first wife of Adam”, created from the same clay as him (and not from his rib, like Eve) and expelled from Paradise for not accepting a subordinate position in relation to man. This image is significant for the meaning of the novel in two senses: firstly because one of the protagonists, Mireia herself, is on several occasions compared to Lilith, for her independence, her beauty, her seductive character and her open sexuality… but also because the representation of women (in painting, literature, science…) almost always from the male point of view is one of its central themes, I would say.

In the main narrative plane, the novel focuses on two women: Neus, the narrator, a young painter, and Mireia, a girl for whom Neus feels an overwhelming fascination. The appearance of a third character, Llorenç, a mysterious man who commissions Neus to paint a portrait, and who begins a relationship (what the film synopsis calls “a torrid romance”) with Mireia. To the tensions existing in this triangle of characters (seduction, jealousy, insecurities…) is added a tone of mystery and danger when strange phenomena begin to occur: a mysterious music that no one seems to play, a man ((or a ghost from the past?) that seems to haunt the protagonists…

Mireia It is a short, agile and entertaining book. Perhaps with a longer length it could have managed to condense some of its many facets (personally, as a horror fan, I would have liked the fantastic part to be a bit more developed and even darker), but in any case the balance between the different threads that are woven into the text is well achieved and maintained, and that is not easy considering their number and diversity. The end of the novel (which I will not reveal, of course) leaves a certain bitter aftertaste, but it also adds new complexities to the characters and the themes of the work.

It is definitely a recommended read, at the very least, whether in its original version in Valencian (or Catalan, depending on terminological preferences), or in the Spanish version published by Dos Bigotes, translated by the author herself.

INTERVIEW

- I start with a curiosity: Is there any relationship between your novel and the Mireia by Frederic Mistral, beyond the coincidence of names?

It is curious, because only you and one other person (a Catalan music critic I met last year at the Ovidi Music Awards) have pointed out this connection and asked me the same thing. And no, the truth is that I did not have that poem by the French author in the Occitan language on my radar. In fact, I looked to see if there was a novel with the same title before betting 100% on it, without thinking that it could have been used for other literary genres. And yes, it turns out that, in 1859, someone had already titled it with that feminine name, so beautiful, by the way… Although one of the reasons, in my case, for titling it Mireia to my novel was its sound similarity to a story by fatal Womandeath and mystery of Edgar Allan Poe that has always fascinated me: Ligeia.

- The novel involves several intertwined plots: the present of the narrator and Mireia, and the life of the psychologist Luis Simarro, son of the painter Ramón Simarro (and his relations with Charcot, Sorolla, etc.). What was the first impulse to write the novel: to tell Simarro’s story, or Mireia’s, or did they both emerge together?

The first impulse was Simarro, because when I started reading about his life I was fascinated by the modernity he represented in a Spain of scientific backwardness and great weight of religion. I could write a biography of this Valencian psychiatrist, but the magic of fiction attracts me so much that I decided to put together a literary device to tell the life and work of Simarro through characters created by my imagination, Neus, the narrator, and Mireia, the researcher in experimental psychology and author of a thesis on Simarro: two young people from the 21st century who become intertwined with the young women from the 19th century that Charcot diagnosed with hysteria. This union of thematic and temporal lines was built in an organic way and also very entertaining for me.

- In the present, the story unfolds like a fantasy tale, with an ambiguity between what is real and what is unreal. Why did you choose that genre or that ambiguity?

Because I love fantasy, gothic literature, scary stories, secluded mansions like Daphne du Maurier, because I grew up reading ETA Hoffmann, Guy de Maupassant, the stories of Emilia Pardo Bazán or the legends of Bécquer, which I knew by heart as a child. And I really enjoy paying homage to all the authors who have made me dream. Besides, what is literature if not ambiguity, in every sense? To force us to look at things in a “straight” way, flat, without chiaroscuro, there are many other cultural discourses. Literature is the queen of the dilogy, of open interpretations, of the perpetual wavering game… And I like it that way.

- The novel deals with various forms of violence suffered by women (through the idea of ”hysteria” for example) and with their representation and subordination throughout history. The character of Mireia is related, for example, to the myth of the fatal Womanof Lilith, of the succubus, of the vampire… Would you say that this is the central theme that unites all the different facets of the text?

Vampire figures come from European oral tradition and are perfectly adapted to Gothic literature: they are beings that live by sucking the life out of humans. And therein lies their metaphorical power: how many vampiric elements surround us, shape us, without us realizing it? MireiaI wanted to play with the figure of the vampire on several levels that the reader discovers as the plot progresses. The iconography of the fatal Woman

The 19th century vampire is directly related to that of female vampires and symbolises the male fear of losing power, of being “sucked” by female power. Mireia could be that strong, independent woman, a 21st century vampire. But little by little we discover other more hidden vampires carried out, without scruples, by men of the 19th century and of the present. And our idea of vampires changes…

- Painting plays a very important role in the novel. Isn’t it a bit paradoxical that the story is told by someone who claims to be not very good with words but is good with paintbrushes?

One aspect that has always fascinated me about the narrators or protagonists of Victorian novels written by women is that they are young girls who present themselves to readers displaying great modesty, displaying a humility that is not in keeping with their true worth. Neus warns us that she is a bad narrator, but she manages to perfectly expose all the threads of a convoluted and complex story. And I think she also manages to hook readers with that thread, something that, in reality, is not an easy thing. So we could say that Neus chooses to be discreet and not boast about her abilities, even though she is as good at the keys as she is with the paintbrushes…

- Another important aspect of the novel is its location, Xàtiva, which is so close and dear to you. What did it mean for you to set the action of the novel in Xátiva, and also to bring back characters who were born or died there?

Well, it has been an act of historical and cultural vindication of my city, but above all, a literary act of love: Xàtiva is another character in the novel and, furthermore, it is presented far from the typical Valencian imagery of “sun, beach and party”. Here it is a sober and mysterious city, with many gothic and modernist touches, with a very nineteenth-century historical density, and the adventures of Mireia and Neus could not have had a more suitable setting.

- The novel was originally written and published in Valencian, and was later translated into Spanish by you. How was that process? Did you do a “pure” translation or did you rewrite the text as you translated it? And how has the book been received in both versions? Have you noticed any differences?

I tried, above all, to make it a translation that was faithful to the rhythm, tone and cadence of the original, because I had taken great care of these aspects in Valencian and I wanted to maintain them. At the beginning of my translation work, it was strange for me to read my text in Spanish, but when I finished the whole process, the impression was great: the truth is that I am very satisfied with how it sounds. Mireia

in Spanish and, honestly, both versions satisfy me equally.

On the reception: it is curious to discover how a small, minority, weaker literary system receives a new text in the literary panorama with greater care and enthusiasm than a macro and ultra-saturated system of novelties such as that of Castilian. And I am not referring to the press or the media: in both languages the attention has been excellent, no complaints. I am referring to the attention of the readers: much more faithful, committed and lasting in Valencian and much more fleeting and dispersed in Castilian. Something completely logical and predictable, taking into account the number of novels that are published in Spain every week… I already think it is quite an achievement to have reached two editions in Castilian with Dos Bigotes after having sold more than three thousand copies in the original…

- Finally, I wanted to ask you what literary or editorial projects you have in the works… You have published books by or about Elena Fortún, as well as an anthology of stories about animals… What are you preparing right now?

I am still, of course, working on new editions for Renacimiento by Elena Fortún. The next thing will be the recovery of a very rare and special book within the Fortunian production… You will see. And in September of this year I will publish a literary essay with Ariel that I have been working on for the last two years: a journey through the narrative written by women that has dealt with portraying oppression within the institution of marriage. A book with a high feminist, humanist and, of course, literary commitment, because the selection of authors is very powerful. And, of course, there are always ideas noted for future projects, both fiction and non-fiction. But you have to find the time, the disposition of spirit and the physical energy to carry them out. Of course, there is no hurry. Just the desire to have a good time.

Source: https://unlibroaldia.blogspot.com/2024/07/resena-entrevista-mireia-de-purificacio.html